Scaling WebRTC media servers in a traditional self-hosted setup can be challenging. For media server providers, it involves complex network management, including handling firewall issues and protecting against malicious attacks on public-facing media servers. As the business grows, additional media servers need to be added, which requires new IP addresses. On the other hand, enterprises that want to use services from media server providers often have strict firewall policies that restrict the use of many ports, especially for UDP traffic. In certain industries, this level of exposure can be a dealbreaker.

The cloud offers a promising solution by placing servers behind a single load balancer. However, Kubernetes—the most prominent platform—is not optimized for WebRTC traffic. Most WebRTC sessions use UDP as the transport protocol, but unlike TCP, UDP is connectionless by design. Moreover, media traffic is usually long-lasting compared to the typical HTTP/TCP response requests for which Kubernetes was designed. Hence routing in the transport layer is unfeasible with traditional load balancers used in Kubernetes.

We want to use Kubernetes because it offers a solution for media servers to scale and deploy on a cloud platform operators aim to reduce the number of firewall exceptions enterprises need to allow to a single IP and port.

This blog post’ll explore the challenges of using Kubernetes for WebRTC media servers, explain how a Kubernetes media gateway can address these challenges, and walk you through our demo project, www.webrtc-observer.org. In this demo project, we'll show how to deploy a WebRTC service in Kubernetes with STUNner multiplexing WebRTC traffic into Kubernetes and use open-source libraries for monitoring WebRTC sessions.

Let’s dive in!

One of Kubernetes' main selling points is its ability to securely host and scale workloads within a distinct, closed perimeter. Typical Kubernetes workloads, like web servers handling millions of HTTP requests, are shielded behind a single load balancer that routes stateful TCP requests to the appropriate server instances. However, this is not the case for UDP-based WebRTC traffic. The issue stems from the way Kubernetes handles networking, which heavily relies on NAT (Network Address Translation) to interconnect pods. This creates problems for WebRTC, as the connectionless nature of UDP makes it difficult to maintain stable sessions. If there are changes in the IP address or port—common when dealing with NAT—the media connections can break, disrupting communications.

To get around networking issues, Kubernetes newbies often switch to node ports and host networking to make servers publicly accessible. However, this approach is both insecure and impractical. First, exposing thousands of ports to the public just to allow access to internal services is off the table in many cases. Consider industries like banking or government, where protecting sensitive data and minimizing attack surfaces are critical requirements. Defending against DDoS attacks and spoofing across hundreds of open port ranges would be unmanageable in practice and is explicitly discouraged by regulations, which require to “limit the number of external network connections to the system”.

Another drawback of sticking to the traditional manual setup is that it keeps the media server instances as unique ‘snowflakes,’ requiring a hand-crafted collection of scripts and step-by-step guides for even the simplest tasks like scaling, upgrades, or failure recovery. Not taking advantage of the automation that Kubernetes offers also limits reaction times to dynamic load spikes or outages. So the question arises naturally: how can we solve WebRTC’s NAT problem in Kubernetes to enable cloud-native deployment of media servers? TL;DR: STUNner the Kubernetes media gateway leverages the TURN functionality! Now, let’s dive into the details.

You’re likely already familiar with the ICE (Interactive Connectivity Establishment) framework, which is designed to find a viable path between peers when direct connectivity is unavailable. ICE relies on STUN and TURN services to connect clients behind firewalls or NATs. For example, if UDP packets are blocked in corporate networks, a TURN server, acting as a UDP relay, can step in as a middleman between the clients, allowing them to exchange data.

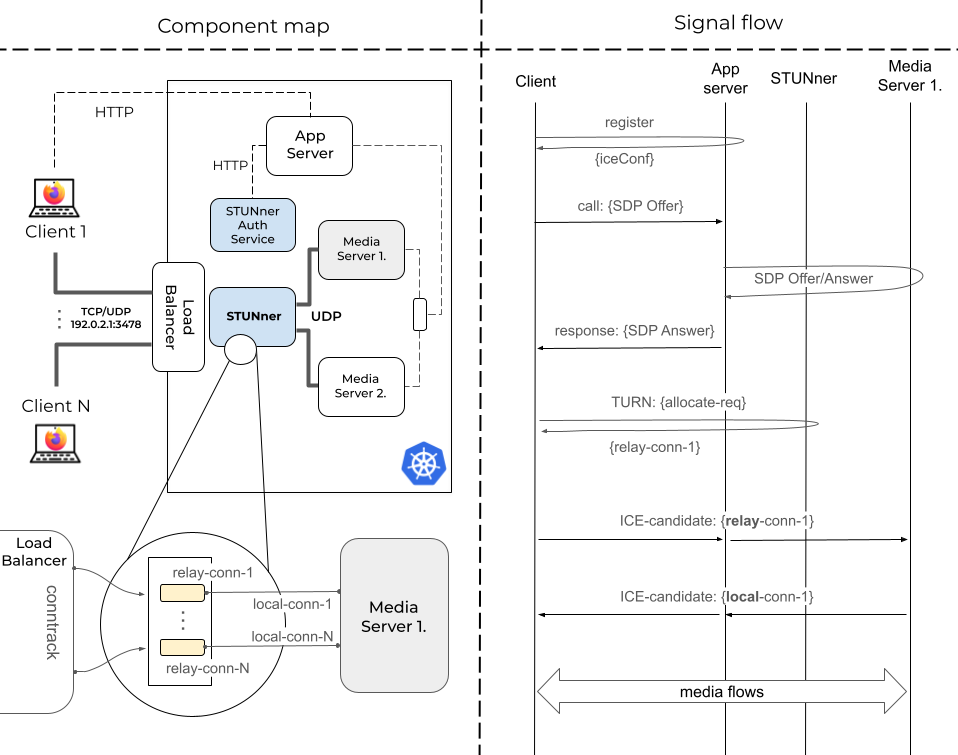

Now, the idea behind STUNner is to repurpose the TURN service as an ingress media gateway for Kubernetes, providing NAT traversal for both clients and media servers. Let’s break down how this works with the help of Fig. 1.

Fig. 1: Key components and steps required to connect a single client to a media server running behind STUNner. Note that media servers can vary, which may result in different signal flows.

The left side gives an overview of the key components. Our WebRTC system runs in a Kubernetes cluster, which includes the Application Server and a fleet of Media Server pods. Clients can access the services through a single IP and port, exposed by a load balancer. The message flow diagram on the right guides us through the steps of the connection setup.

The first step for clients is to register with the Application Server, and in return, they receive the ICE configuration, which lists STUNner as the sole TURN server, along with the necessary TURN credentials (Fig. 2). But how does the Application Server know the public IP of the Load Balancer and the TURN credentials? This is where the STUNner Auth Service comes into play by keeping track of these variables and providing them through a REST API.

{ |

Fig. 2: The ICE configuration returned by the Application Server. Note that transport can be TCP as well, and a single response can contain both settings.

When Client 1 wants to join a video conference, it notifies the Application Server with a call message that includes its SDP. The Application Server forwards this offer to a selected media server, let’s say Media Server 1, and returns the generated SDP answer in the response message. This, of course, means the Application Server must track user sessions and media server instances to route incoming sessions to the least loaded media server.

At this point, Client 1 is aware of the media descriptors and the next hop needed to establish connectivity with Media Server 1, which is STUNner! The client sends a TURN allocate request, which STUNner acknowledges by providing the details of the relay connection. Note that this is a private IP address, as the internal leg of STUNner connects to the Kubernetes CNI. However, since the media server pods also reside in the cluster, thanks to Kubernetes networking principles (all pods can communicate with each other without NAT), the ICE connectivity check completes successfully, allowing media packets to traverse between Client 1 and Media Server 1!

Fig. 3: Architecture of the www.webrtc-observer.org demo application in Kubernetes, highlighting the external and internal ports, protocols, and the sampling points associated with the measurements visualized in Grafana.

We developed www.webrtc-observer.org to showcase various use cases of the ObserveRTC open-source WebRTC monitoring toolkit. The demo platform runs on Kubernetes (deployed in Google Kubernetes Engine). It uses the STUNner media gateway to ingest the WebRTC traffic into Kubernetes seamlessly. The source code is available on GitHub.

apiVersion: apps/v1 |

Snippet 1. YAML script describing the media server in Kubernetes. The full script is here

The system combines the media and app server functionalities into a single microservice, deployed using a Kubernetes Deployment resource YAML (Snippet 1.). The deployment defines the number of replicas, ensuring scalability. When the Media Server instances start, they automatically discover and share information through Redis using Hamok. This enables media transports to dynamically establish connections between different media server instances when participants in a call are connected to separate instances.

The Media Server leverages mediasoup to provide WebRTC SFU functionality. Mediasoup enables WebRTC peer connections via its WebRtcTransport object. Typically, each WebRtcTransport requires its own dedicated server port. However, by utilizing a WebRTCServer, multiple WebRtcTransports can share a single UDP/TCP port.

This setup centralizes network traffic handling, eliminating the need for each transport to listen on its own IP address and port. As a result, all network traffic for one CPU core can be multiplexed into a single port per instance. Utilizing this, the service allocates two CPU threads per instance and exposes UDP ports 5000 and 5001 within the Kubernetes cluster to handle RTC traffic on each media-server pod.

apiVersion: gateway.networking.k8s.io/v1 kind: Gateway metadata: name: udp-gateway namespace: default spec: addresses: - value: {{ .Values.publicIP }} type: IPAddress gatewayClassName: stunner-gatewayclass listeners: - name: udp-listener port: 3478 protocol: TURN-UDP --- apiVersion: stunner.l7mp.io/v1 kind: UDPRoute metadata: name: mediaserver namespace: default spec: parentRefs: - name: udp-gateway rules: - backendRefs: - name: mediaserver-media namespace: default |

Snippet 2. YAML script describing key STUNner components. The full script is here

The next step in the setup involves multiplexing all pod-exposed ports (UDP 5000 and 5001) into a single Kubernetes service entry point (mediaserver-media). This cluster-internal service is configured as a backend for STUNner (see UDPRoute configuration in Snippet 2). STUNner initiates a standard Kubernetes gateway (called udp-gateway) to connect this service to the outside world. The gateway is configured with a UDP listener that acts as a TURN server for the clients on the UDP port 3478 (Snippet 2). The full script creates all required resources in less than 50 lines of code.

When a client establishes a WebSocket connection, the service acts as a signaling server, facilitating RTC capabilities. During this process, the media-server retrieves TURN credentials from the STUNner authentication service and provides it to the client with the capabilities. The media server's provided IP and port correspond to the pod's internal Kubernetes cluster IP, requiring the client to connect via TURN. The TURN URI includes the public IP of STUNner, enabling the client to initiate ICE negotiation.

The ICE negotiation is conducted with STUNner, which acts as a relay. It forwards media traffic between the client and the appropriate pod assigned to handle the media. This setup efficiently manages NAT traversal and ensures seamless media traffic routing in a Kubernetes environment.

Once the PeerConnection is established and media flows correctly, the service becomes a fully scalable media provider behind Kubernetes. The standout feature of this setup is its simplicity and efficiency: no matter how many media servers are added, all client media connections are managed through a single IP address and port. This approach maximizes scalability and minimizes complexity.

Fig. 4: The ICE candidates visualized in the web application: The app & media servers on the right are running in Kubernetes. Clients access them via a single TURN/UDP port exposed by the STUNner media gateway. Dashed lines represent the signaling over HTTP/WS.

Figure 4 shows a straightforward representation of this approach. On the right side of the figure, we see the two media server instances running in Kubernetes. The clients connecting to these media-server pods are on the left. The media connectivity between the two entities goes through a single IP address and port via STUNner. The dashed lines are "virtual links" showing which media server instance the client connects.

When it comes to using STUNner, a metric of particular interest is the additional latency introduced by STUNner as it acts as a gateway for media servers. Quantifying this latency is crucial to understanding its impact on overall call quality and optimizing performance in real-world scenarios.

An educated guess is that adding an extra TURN processing to the media data plane is a luxury since it adds extra latency. We instrumented STUNner to measure packet processing times (see the red dots in Fig. 3) to make this extra cost quantifiable. We expose these metrics in an embedded Grafana dashboard under the 'Learn more about STUNner' page.

This dashboard presents the averaged packet processing time. A gauge shows the average last minute, while the time series plot details the history. The dashboard also displays the throughput averaged for the last minute and the number of active connections.

Fig. 5: STUNner performance metrics: packet processing delays, throughput, and number of active connections. The dashboard is visible under ‘Learn more about STUNner’ on the website.

As Figure 5 shows, the packet processing delays are almost negligible. We see a slight increase when a new client connects. However, this spike disappears as the TURN signaling is over, and STUNner relays media traffic only.

It's time to wrap up our Kubernetes journey. In this blog post, we first learned about the challenges of deploying WebRTC applications to Kubernetes. We have seen how the STUNner media gateway exposes our WebRTC services with the help of the good old TURN and some Kubernetes Gateway magic. STUNner uses a single IP and port to ingest all media traffic and secure our deployments. So far, this is a fairy tale, but what about performance? We developed a mediasoup-based demo project to measure performance metrics. We use ObserveRTC and cloud-native monitoring tools to quantify the STUNner overhead. Our results show the STUNner overhead is negligible. Meanwhile, we can obtain meaningful statistics with ObserveRTC in Kubernetes, too.